The Meatless Burger Arrives

For the last year, late-night revelers who wander into the nearest White Castle restaurant after closing down a nearby drinking establishment have been confronted with a menu advertising the “Impossible Slider.” This is a plant-based burger from Impossible Foods, and it made the jump last year from high-end restaurants with locally sourced ingredients like Founding Farmers in Washington, DC to national chains like White Castle and Burger King.

2019 will likely be remembered as “the year of the meatless burger.” Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods achieved significant media attention and reached record numbers of consumers, including many from the meat-eating public. In fact, about 95% of people who purchased a plant-based burger this year were meat eaters, according to market research from NPD Group.

With the successful launch of plant-based burgers in Burger King, White Castle and other fast food chains, millions of servings of plant-based burgers were purchased last year. Livestock producers need not fret quite yet, however. Despite the uptick in interest in plant-based burgers, NPD says that annual consumption of beef burgers remains stable at nearly 6 and a half billion servings.

But Who Said The Meatless Burger Is Healthier?

Despite the fact that most American adults get plenty of protein in their diet, 61 percent told NPD they want even more protein. Interest in plant-based burgers then builds on the years-long trend of consumers searching for higher-protein diets. The meatless burger delivers protein with a perceived plus—according to NPD, many people believe plant-based proteins to be better for you.

In this significant and erroneous perception, we have the subject of today’s post. A meatless burger sounds like a healthy choice, but is it really? Did the manufacturers even claim that it was healthy, or did we all just assume it? The truth is that the nutritional profile of plant-based burgers is relatively close to beef burgers with respect to dietary concern factors such as sodium, calories, and fat content. Alas, turning to plant-based protein may appeal from an environmental or moral standpoint, but it does not suddenly solve all our diet problems.

One Virtue Doesn’t Mean All Virtues

Many consumers today are buying plant-based foods for health reasons, just as consumers have long bought salads because they wanted to make the healthy choice. Unfortunately, our brains often have other plans for us. Good diet decisions are not quite as simple as we’d like them to be. As discussed in the article on “Decision Fatigue”, we use mental shortcuts to get through our busy days and make our numerous decisions more efficiently, especially when it comes to food. For example, we may choose a healthy snack such as an apple so that we don’t have to worry about counting calories—but the fact is that the apple still has calories. We may virtuously choose the salad rather than a burger—but a salad with dressing may still carry a lot of fat. When we consider a particular food to be healthy in some respect, our brains all too often completely disregard all its other dietary baggage. When it comes to our diets, we tend to treat healthy foods as if they can do no wrong. This is called the “health halo effect,” or simply the halo effect. It’s another classic mental shortcut that sometimes short-circuits our efforts to build a truly beneficial diet.

The Halo Effect—A Natural Bias

The halo effect is an error in perception that distorts how we see other people, companies, or products. More specifically, “the halo effect is the tendency for positive impressions of a person, company, brand or product in one area to positively influence one’s opinion or feelings in other areas.”FN1 The halo effect helps explain why first impressions are so important. We have all experienced, and been influenced by, the halo effect at one time or another. When we see a photograph of an attractive person, we tend to ascribe other positive qualities or traits to the person as well, perhaps thinking of them as a good, smart or successful person. Juries are more likely to go easy on attractive defendants and companies are more likely to hire them. As we explain in the article on “Naturalness Bias,” a single word can have a powerful halo effect: We tend to impute positive qualities to food that features the word “natural” in its labeling, even if those qualities are imaginary.

The halo effect comes from our brain wanting things to be nice and simple, so its endless decisions about what to do can be easier. Our brain wants to hurry up and classify things as good or bad, beneficial or harmful. Unless we pay attention, it will take the quickest and easiest way to get there. Our mental autopilot will overlook complicated truth in favor of a reassuring simplification. When this happens, accurate perception gets left behind.

We Simplify The Truth As A Shortcut

When applied to food, the health halo effect refers to the way we overestimate the healthfulness of an item based on a single factor or claim, ignoring other relevant information. This may occur when we see a food labeled as natural, gluten-free or low-fat. For example, studies have shown that consumers sometimes confuse “low-fat” with “low-calorie”, which can lead them to over-consume foods labeled low-fat. The low-fat label gives us permission to eat more than we otherwise would because we feel better (or less guilty) about the decision since we assume the food is also low in calories. Research suggests that this tendency is even stronger for those of us who need to watch what we eat. Our overworked brain wants things to be simple, so it equates low-fat with “good,” and under the halo effect it then treats the food like it can do no wrong no matter how much of it we consume.

Halo Effect Assumptions Mislead Us

Research on the impact of front-of-package labeling of proteins bars also found a significant halo effect connected to the word “protein” on consumer perception of the healthfulness of the product. The presence of “protein” in the name of the product not only influenced perceptions of protein content, but it also increased consumer perceptions of fiber and iron content in the bar—which are totally unrelated dietary concern factors. The presence of a health halo effect was quite clear.

Health halos also influence our judgments about restaurants. If we believe we are eating at a healthy restaurant, we tend to assume all the food they serve is healthy. For example, consumers associate Subway with fresh and healthy food, which is how the company positions itself in marketing. By contrast, consumers would not tend to associate McDonald’s with healthy food choices. Researchers have found that people buying food at Subway were less accurate at estimating the calorie and sodium content of their meals. The same study found that when people thought they were making healthy meal choices, they were more likely to add toppings, drinks, and desserts, which, in some cases, doubled the calorie count of the meal. This tendency or bias occurred even for consumers who reported that they were trying to make healthy food choices.

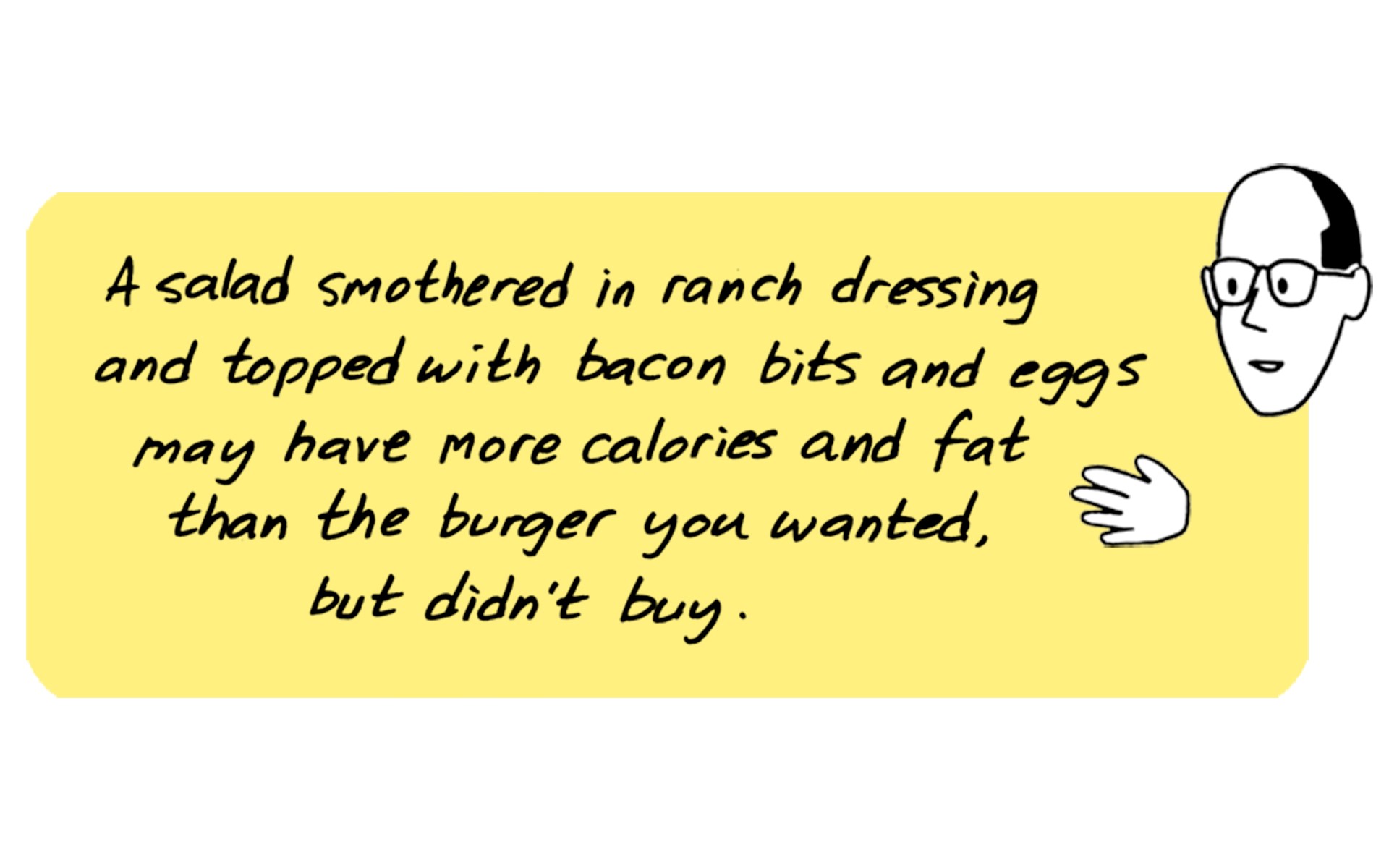

Seeing The Truth Beyond The Halo

The virtue of mental shortcuts is that they remove the drudgery of making innumerable decisions each day. The problem, of course, is that many decisions that are made on autopilot should be given more attention because the default choice often is not the best for our health or happiness. Buzzwords like ‘protein’, ‘plant-based’ and ‘organic’ are regularly used in food marketing campaigns as key features or selling points of a product because they have a health halo. Such words can fool consumers into thinking that a product is healthier than it really is, which can lead people to make less healthy choices. It is important to remember that a salad smothered in ranch dressing, topped with bacon bits and eggs, may have more calories and fat than the burger you wanted, but didn’t buy.

So how do you avoid falling into the health-halo trap? Awareness is key. You have to take your mind off autopilot to establish good food choices as your habits. Remember that what goes on the front of the package is generally the information the food company wants you to know, while the information on the nutrition panel is what FDA and registered dietitian nutritionists want you to know. This includes the recommended serving size for the food. Low in fat could mean high in calories. Low in sodium might mean high in fat. Unless you have an allergy or food intolerance, gluten-free usually just means more expensive and less tasty. Instead of allowing healthy-sounding terms to put you at ease, you should think of them as a warning sign to pay extra attention and determine whether the food really will help you build a healthy and beneficial diet.

A Little Attention Will Build Healthier Habits

The moral of the story here is that taking shortcuts is going to cost you one way or another. You make countless food decisions in the course of your life. Most of them are habit-based, made without much thought. Take the time to pay attention, and to understand what is really good for you, instead of breezing through choices that will have a real impact on your body and your quality of life. Try consulting with a registered dietitian. Once you’ve identified what is truly best for you, you can turn the autopilot back on, and relax in the confidence of having established healthy food-buying habits. You’ll be making good choices instead of buying into the appealing, but often misleading, halo effect.